Summary

A quasi-experiment conducted to quantify the causal impact of music sessions with very low income older adults revealed significant positive effects on a wide array of measures spanning physical, emotional, cognitive, and social engagement dimensions, including outcome metrics that increase residents’ chances of thriving in an independent living setting. Compared to matched control subjects, music participants reported improved sense of community, higher community trust and engagement, improved physical health, more physical exercise, better word recall, and less hopelessness and signs of depression. While matched control subjects felt older and experienced more severe chronic pain at post-intervention time point, the same declines were not observed among music participants. Evidence from this research could be instrumental in influencing HUD funding allocations to include arts engagement programs shown to improve health and wellness in low-income communities.

In the past fiscal year, the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) had disbursed $749 million in housing assistance grants in support of the Section 202 and Section 811 programs. While HUD is invested in its mission to help residents continue to live in this independent setting, the agency does not currently fund any kind of arts intervention program in its housing projects. The main impediment is HUD lacks compelling evidence that arts programming can promote health and wellness among very low-income older adults, and thereby reduce the high costs of medical treatment and institutionalization.

This lack of evidence observed by HUD is a legitimate concern. Two recent literature reviews of research conducted with older adults actively engaged in dance, music, creative writing, theatre, or visual arts revealed evidence of positive outcomes in quality of life, emotional well-being, and cognitive functioning (Fraser et al. 2015; Noice et al., 2014), but the vast majority of studies were not built on experimental design or standardized measurement. Furthermore, literature reviews cannot overcome the publication bias, whereby researchers are more likely to seek publication of studies that produce positive or significant findings, while data with null effects are buried and forgotten.

A previous analysis of a large-scale nationally representative sample (drawn from the Health & Retirement Study 2014) that revealed a clear socioeconomic divide in creative aging – namely, that access to the creative arts is a social privilege of people who are more wealthy and educated. More importantly, when older adults in the lowest income and education groups get to participate in the creative arts, they often manifest the most significant uplifts in well-being (Chang, 2016). However, this analysis was conducted on cross sectional survey data that precluded causal inference. In contrast, causal inference from quasi-experimental designs can be strengthened by taking concurrent measurements of a matched control group (Rubin, 1973), whereby matching treatment subjects to control subjects with similar attributes, we can test and quantify the treatment effect with minimal confounds.

The sample for this research was drawn from older adults dwelling in 1 of 20 HUD Section 202 housing properties for very low-income elderly persons. The majority of residents live alone in 1-bedroom apartments; married couples share similar 1-bedroom apartments. The 20 properties include 10 intervention sites where weekly music sessions were held for 3 consecutive months, and 10 matched control sites where residents received no exposure at all to on site music activities. The properties were matched on commonalities on site parameters including geographic region (e.g. midwest vs. northeast), median age, gender ratio, racial composition, percent of frail residents, and percent of married residents. In January 2018, baseline data was collected concurrently from residents at 10 intervention sites and 10 control sites. Music sessions were conducted at the 10 intervention sites from February to April 2018; and the post-intervention data was collected in May 2018.

In order to make causal inferences of the impact of music participation, 135 matched control subjects were drawn from the 10 control sites. The control subjects were matched to the 135 music participants based on individual attributes including gender, age, race and ethnicity, education, marital status, and self-assessed personal health status. Controlling for these individual attributes as well as site characteristics allow us to make inferences about what these residents would have experienced if they did vs. did not have the opportunity to participant in weekly music engagement programs.

A total of 135 unique residents across 10 sites attended the weekly sessions. It was apparent that some residents loved the music sessions while others did not take to it much. As shown below, about 1 in 4 participants attended the music sessions and never came back; but about 1 in 4 residents attended the music sessions all 10 times. The remainder of residents fell somewhere in between.

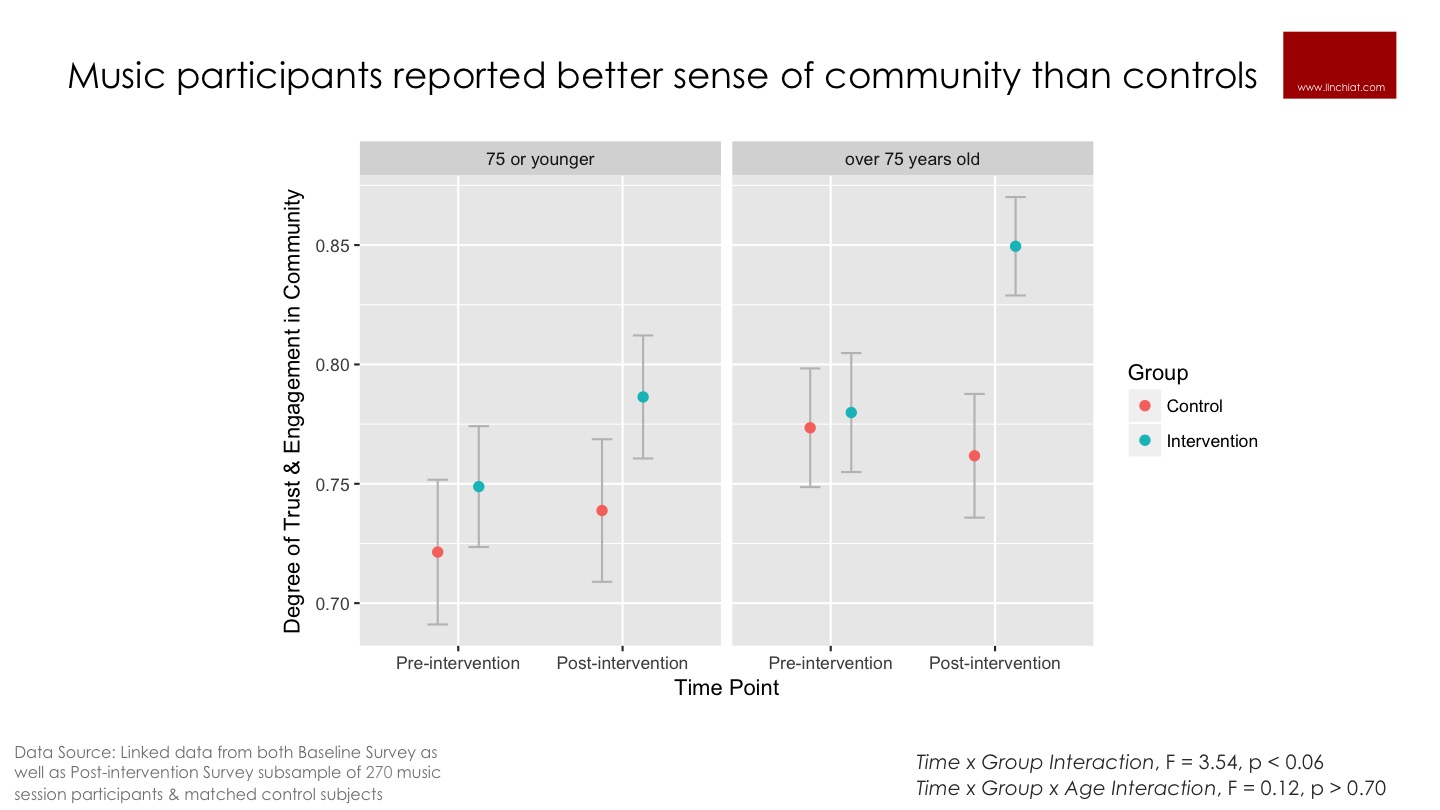

Community engagement was assessed with a general measure of perceived change; as well as a 4-item composite index taken at baseline as well as post-intervention time points. The general measure of change simply asked residents compared to January 2018, has the sense of community in the building gotten better today, about the same, or worse? Results are shown in figure above. Music participants reported significantly improved sense of community than controls before vs. after intervention, X-squared = 26.2, p < 0.001.

The 4-item composite index included the extent to which people in the community help each other out, extent to which there are people one could count on in this community, the extent to which people in this community can be trusted, and perceptions of the degree to which there is a close-knit community on site. These 4 items were correlated between 0.39 to 0.53; and yielded a satisfactory Cronbach’s alpha of 0.77 (lower bound alpha = 0.74, higher bound alpha = 0.80 at 95% confidence interval). Hence these 4 items were combined to form one composite index of community trust and engagement. These items were measured twice – once at baseline, and once at post-intervention – in order to detect any changes in residents’ perceptions of community trust and engagement. A positive effect emerged on this index, such that music participants reported significantly improved sense of community than controls before vs. after intervention, 2-way Time x Group Interaction F = 3.54, p < 0.06. As shown in figure above, intervention site residents showed significant uplifts in their perceptions of community trust and engagement, while control site residents showed no significant change in perceptions. Although the effect sizes suggest more pronounced impact on residents over 75 years old than residents 75 or younger, the interaction effect with age did not reach statistical significance, 3-way Time x Group x Age Interaction F = 0.12, p > 0.70.

Physical health was also with a general measure of perceived change in self-assessed health status; as well as repeated measures of self-perceived age, common chronic conditions, chronic pain, sleep issues, hearing, exercise, smoking, alcohol intake, need for prescription medications, etc. The general measure of change simply asked residents compared to January 2018, has their health gotten better today, about the same, or worse? Results are shown in figure above. Music participants reported significantly improved health than controls before vs. after intervention, X-squared = 13.1, p < 0.001.

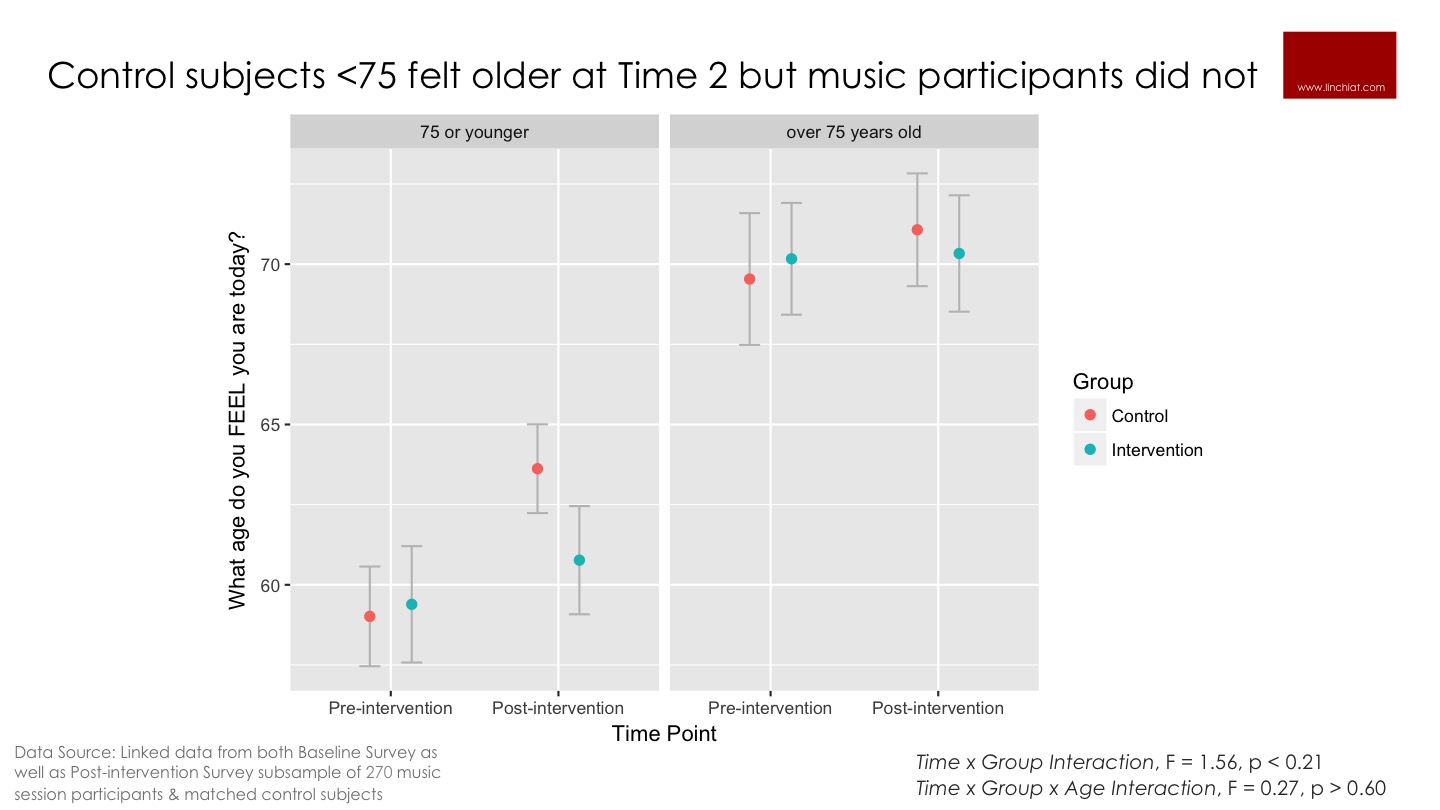

Another measure of perceived physical well-being is to ask people what age they feel they are at today, regardless of their actual age. This item was measured twice – once at baseline, and once at post-intervention – in order to detect any changes in residents’ perceptions of their own age. Although no significant positive effect emerged on this measure for intervention subjects, a significant negative effect was observed among the matched control subjects, such that control subjects younger than 75 felt older at the post-intervention time point, pairwise contrast t = 56.6, p-value < 0.001. This effect suggest that even though regular music activities did not make residents feel younger, it is likely that they would had felt older in the absence of those activities.

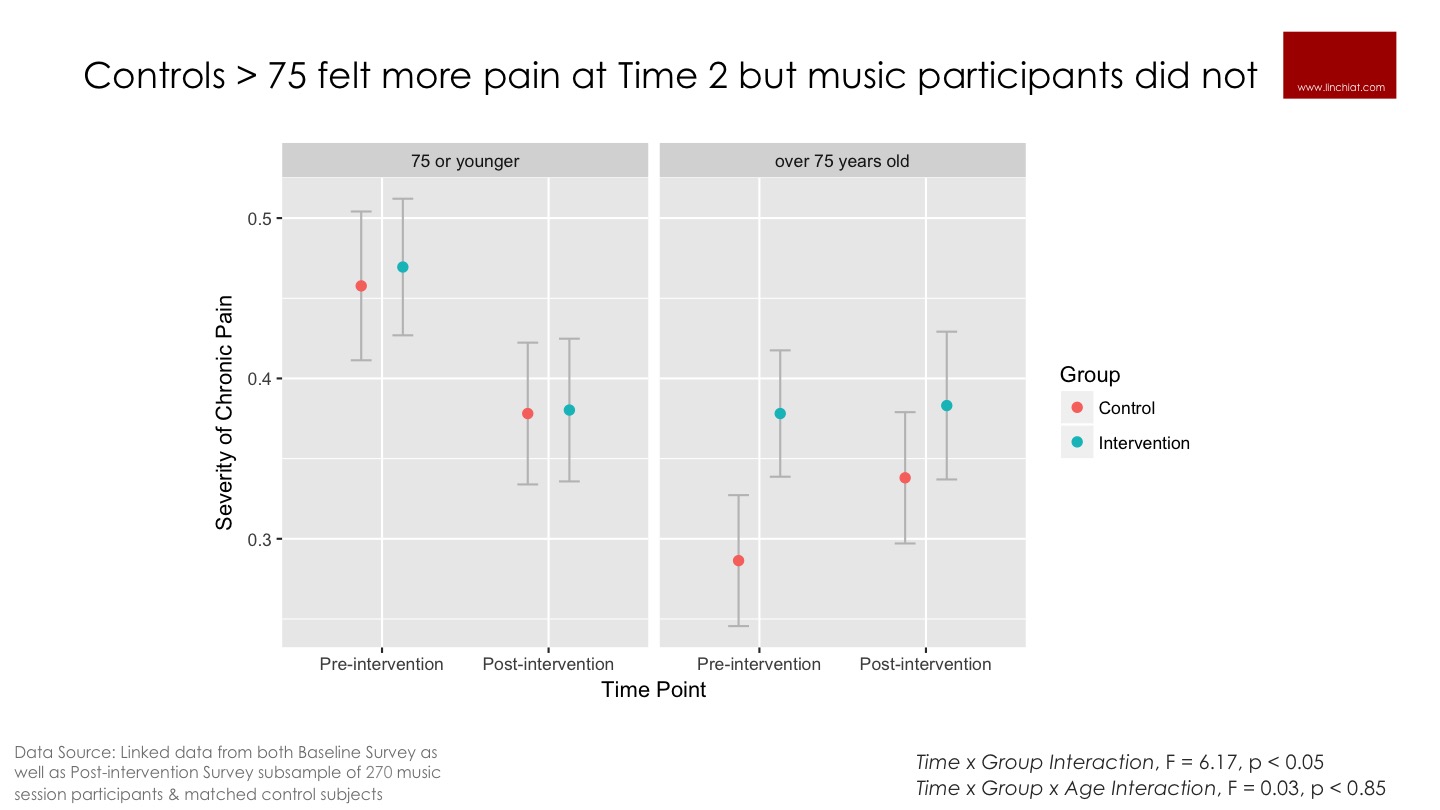

A similar effect emerged on the measure of chronic pain. All subjects 75 or younger reported less chronic pain post intervention, reflecting no intervention effect for this age group. Although no significant positive effect emerged on this measure for intervention subjects older than 75, a significant negative effect was observed among the matched control subjects, such that control subjects older than 75 reported more sever chronic pain at the post-intervention time point, pairwise contrast t = 1.98, p-value < 0.05. This effect suggest that even though regular music activities did not make residents feel less pain, it is possible that those older than 75 could had felt more pain if they did not had the opportunity of participating in music programming on site in their communities.

A strong intervention effect emerged on the measure of physical exercise, regardless of age groups. Music participants at the intervention sites reported engaging in more moderate exercise than control subjects – i.e. they reported more days in the past week when you had walked or exercised or moved in ways that caused light sweating, or moderate increase in breathing or heart rate, 2-way Time x Group Interaction F = 7.99, p < 0.005. As shown above, these differences between the 2 groups at the 2 time points of interest – at January 2018 baseline prior to launch of music sessions, both intervention and control groups showed about the same levels of moderate physical exercise. In contrast, in the post-intervention time point of April 2018 after they had participated in regular music sessions, the intervention subjects reported elevated levels of moderate physical exercise, compared to both control subjects as well as their own baseline 3 months ago. This uplift in physical activity was evident in both age groups and therefore not moderated by age at all, 3-way Time x Group x Age Interaction F = 0.27, p > 0.60. In short, the elevated levels of moderate physical exercise among intervention subjects is a robust effect regardless of age.

At both pre-intervention and post-intervention time points, residents were tested on their actual word recall based on a standardized test routinely used in the Health & Retirement Study. In essence, the interviewer reads out a set of 10 simple words, and then ask the respondent to try to recall aloud as many of the words as they can, with assurances that most people recall just a few words in order to alleviate performance anxiety. Different set of words were used at pre-intervention and post-intervention time points, but the same set of words were asked across intervention and control subjects. As shown above, a significant intervention effect emerged on this measure, such that intervention subjects age 75 or younger showed marginal improvement in their word recall, 3-way Time x Group x Age Interaction F = 3.49, p < 0.06.

Emotional well-being measures included asking how often residents felt depression, anxiety, worry and fears, anger, fatigue, feelings of worthlessness, hopelessness, loneliness, regret etc. during the past 30 days. These measures were repeated at both pre-intervention and post-intervention time points to test whether participation in the music sessions would reduce frequency of emotional distress. A positive intervention effect emerged on feelings of hopelessness. Music participants at the intervention sites felt hopeless less often than control subjects at post-intervention, 2-way Time x Group Interaction F = 5.19, p < 0.05. This uplift in hope, or decrease in feelings of hopelessness, was evident regardless of age.

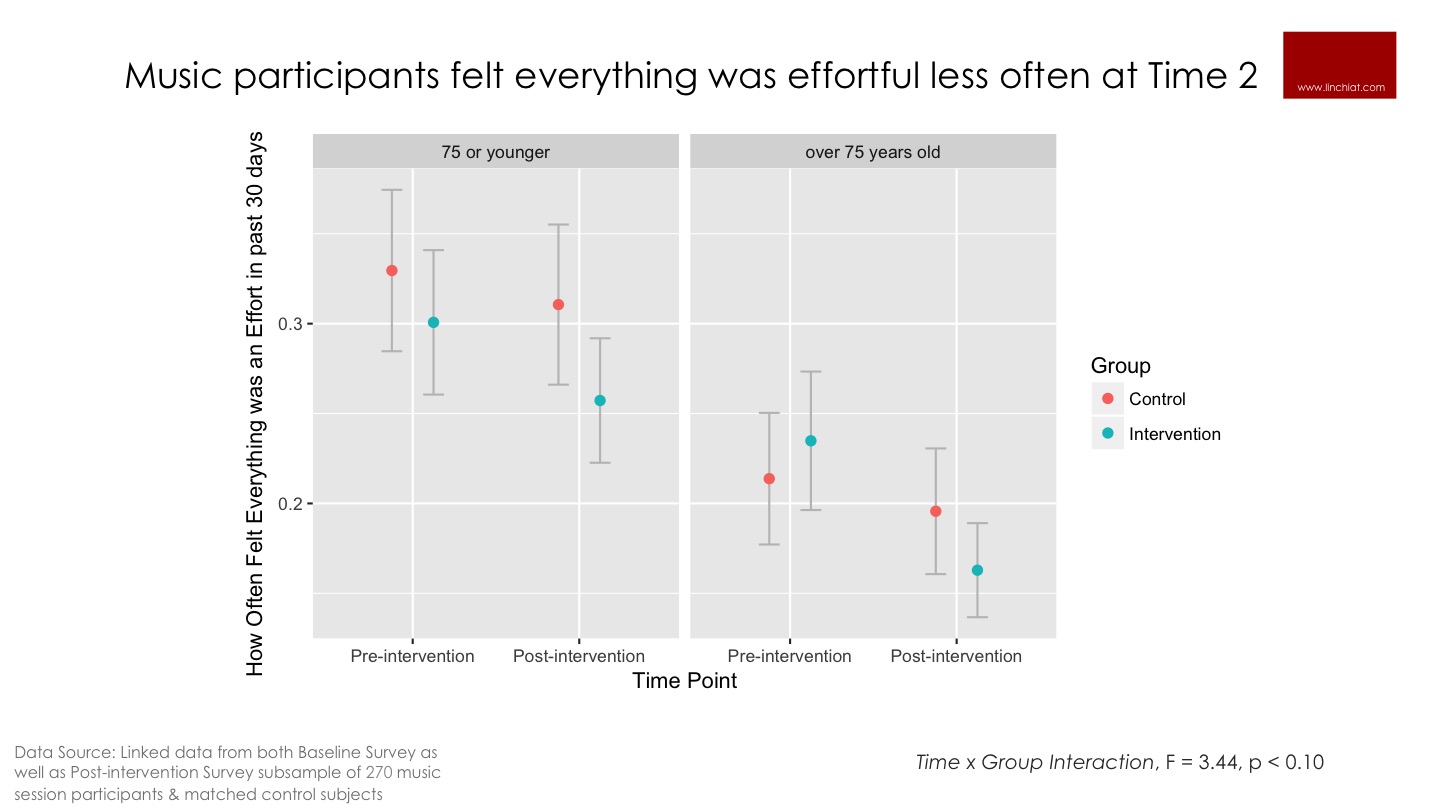

As shown above, a similar pattern emerged on the frequency of feeling that everything was an effort, a strong proxy of depression and poor physical and emotional health. Although the trends are consistent, the effect size only reached marginal statistical significance, 2-way Time x Group Interaction F = 3.44, p < 0.10.

Other intervention effects emerged on only one age group and not both. For example, in feelings of anger, intervention subjects over 75 felt angry less often after participation in the music sessions, but the same effect did not emerge among intervention subjects 75 or younger. A similar pattern emerged on feelings of anxiety. Intervention subjects over 75 felt nervous less often after participation in the music sessions, but the same effect did not emerge among intervention subjects 75 or younger. A similar pattern emerged on feelings of worthlessness. Intervention subjects over 75 felt worthless less often after participation in the music sessions, but the same effect did not emerge among intervention subjects 75 or younger. Taken together, it is evident that music participants age over 75 reaped much more emotional benefits from the music sessions than their younger counterparts. Data was also collected on other measures of emotional well-being, including sense of purpose in life, internalization of the social stigma of aging, feelings of joy, hope, self-efficacy and mastery. No significant intervention effect was detected on any of those measures, all p > 0.30.

Correlation cannot establish causation. In most past research, arts participants could just be healthier and better adjusted anyway, and the arts had no real impact on their well-being. Comparing music sessions participants vs. matched control subjects in this quasi-experimental design allow us to isolate and quantify effect of creative arts participation, because the matched control subjects reflect where intervention subjects could still be if they did not have the opportunity of engaging in regular music sessions. As shown above, pre vs. post intervention measures across a wide array of physical, emotional, cognitive, and social engagement dimensions revealed significant positive effects of participation in the music sessions, particularly on outcome metrics that increase residents’ chances of thriving in an independent living setting.

Source: Chang, LinChiat, Helen Kivnik, Linda Davis, Betty Montgomery and Judith-Kate Friedman. 2018. Impact Assessment of Music Engagement Programs and Vital Involvement Model on Low-income Elders in Subsidized Housing Communities. NEA Research Report. Parts of this research was presented at the 2018 Gerontological Society of America's 70th Annual Scientific Meeting, as well as the 2019 Aging in America Conference.

This analysis was supported in part by an award from the Research: Art Works program of the National Endowment for the Arts: Grant #14-3800-7008. The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not represent the view of the Office of Research & Analysis or the National Endowment for the Arts.

We are grateful for the hard work and support of many wonderful people who made this study possible, and want to express immense gratitude and thanks to the following heroes:

Service Coordinators at the 10 intervention sites who did the bulk of data collection and data entry for this research, on top of meeting demands of active coordination of weekly music sessions - Donna Beatty, Josie Calderon, Laura Tazi, Lisa Vasquez, Mary Lutterman, Ruth Roberson, Sara Scott, Sherrie Hank.

Service Coordinators at the 10 control sites who did the bulk of data collection and data entry for this research - Barbara Brownell, Kaitlyn Hohnstrater, Peggy Howard, Rashenda Johnson, Robyn Steffen, Robyn Steffen, Tammara Deleston, Taylor Martinez, Taylor Martinez, Theresa Jones.

Colleagues who stepped up to assist Service Coordinators on some sites that were overwhelmed by the volume of work required in data collection and data entry - Bridgette Carter, Carol Byers, Elizabeth Gilchrest, Elyse Franceschi, Jessica Castillo, Katherine Bemont, Robin Walker.

Amanda Kline who set up Google online forms for data entry at both pre-intervention and post-intervention time points, and provided invaluable technical assistance throughout the process.

Exemplary musicians who led the weekly songwriting sessions on site: Don Strong (Minnesota), Hogan and Moss (Texas), Jessie Ritter (Alabama), Krista Detor (Indiana), and Sally Rogers (Connecticut).